Chapter 3 | FORESHORTENING

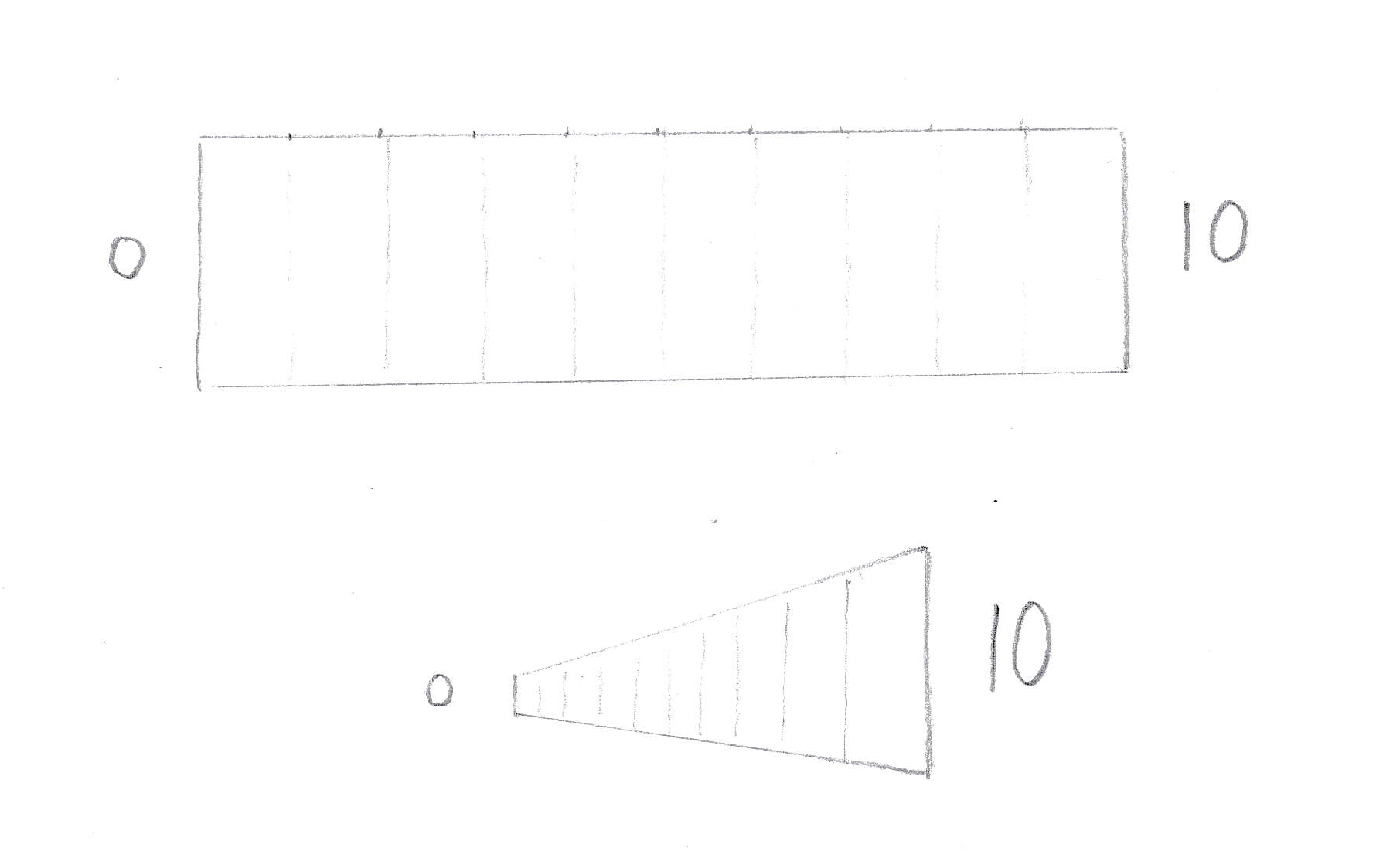

Suppose you look at a ruler straight from the front, at its full length, and you will clearly see that the ten centimeters are the same size. If you see the ruler in perspective, the back centimeters become smaller and smaller (image). In perspective, the ruler becomes foreshortened.

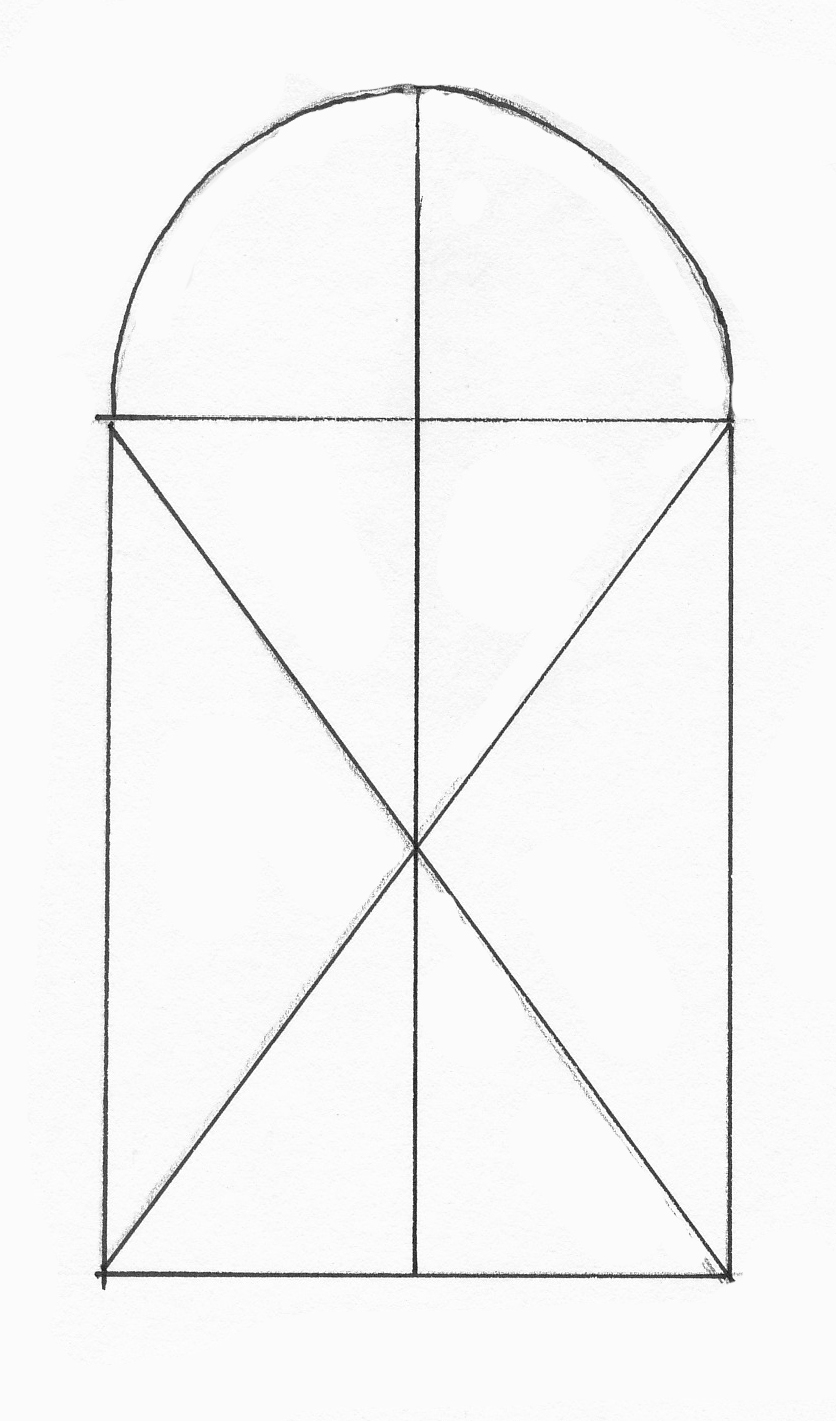

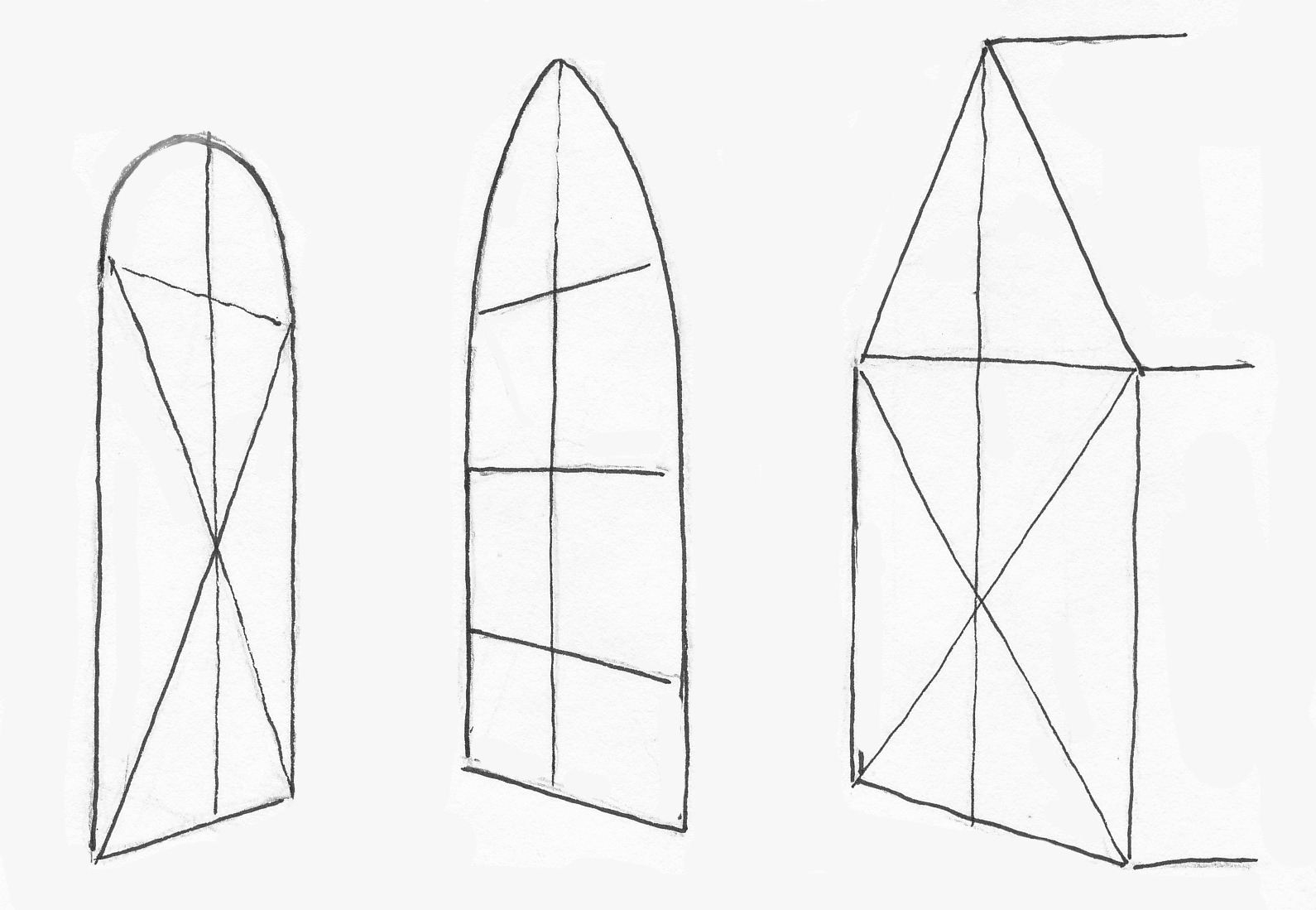

If we see for example a window perspectively shortened and not straight from the front, the back half is further away than the front half and therefore becomes slightly smaller/narrower in the drawing. In such a case you can find the center with the help of two diagonals. In the following drawings I will show you how that works. This way you can easily find the center of each plane in perspective.

Exercise: Draw a round arched window, a pointed arched window, and the facade of a house with a pointed roof in perspective. Keep in mind that the original horizontal lines should converge to the same vanishing point, either to the right or left of the window.

Arched windwo from the front

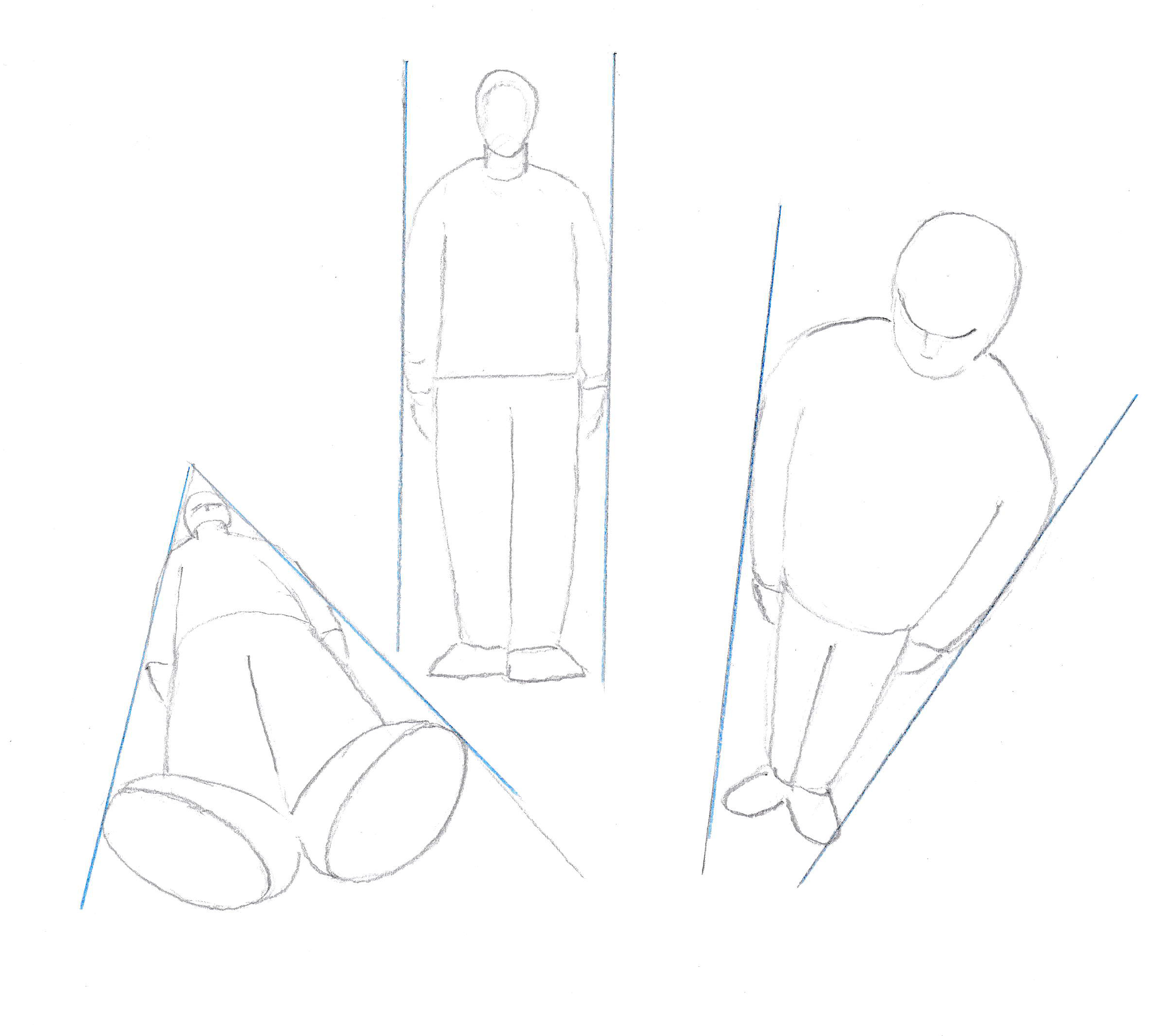

Of course, foreshortening does not only apply to straight rectangular objects. For example, figures that we see from above or below will also become foreshortened in perspective. The part further away becomes relatively much shorter.

The most famous form of perspective foreshortening is the Italian “Di sotto in su,” which means “From Below to Above.” If you look up at the ceiling of the wedding hall of a palace in Mantua, Italy, you’ll see a painted (!) opening to the outside. Along the walls of the opening are cherubs seen from below, di sotto in su. Leaning over the edges, curious spectators gaze at the bride and groom and the guests below. In this way, the painter Andrea Mantegna created a festive illusion.